Greetings,

The short version—no one needs the long version, least of all me—is that I have a beautiful, eccentric collection of books (photography, art, illustrated history, books about Hollywood, books about places, etc.) for sale. (See tag: Economic Reality.)

Below is a list and a brief description of condition, etc. I’m sure I’ve not adhered to the conventions beloved of antiquarians (anyway, they’re not antiques) and book dealers, but it’s a start. Assume DUST is another adjective applicable to the books! (When I say ‘shelving wear’ I mean the marks that you get from storing books beside one another.)

Willing to do small number of photos of selected titles if you ask nicely, or arrange a visit if you’re a dealer who’s interested. I’d like to sell the books as a job lot, though willing to consider other arrangements. BUYER MUST ORGANISE UPLIFT. The books are too heavy to post.

Primarily hardcover with paper jacket except where noted

FIRST EDITIONS US or UK:

Bruce Weber photographs

Borzoi, 1988, FIRST EDITION,

no paper jacket, signs of wear to binding commensurate with age but overall very good condition

The Audrey Hepburn Treasures, Pictures and Mementos from a Life, by Eileen Erwin and Jessica Diamond

S&S, 2006 FIRST EDITON, 192p, published without a jacket, so images printed onto boards

Scuffing and damage to upper corner by spine at back, and other lighter signs of wear; book was created with inserts kept in glassine envelopes, so the edge is slightly more compressed than it is at the spine side. Contents complete.

English Style, Slesin & Cliff

Clarkson Potter, FIRST EDITION, (US) 1984, 289p

Good condition, light signs of wear to jacket

Italian Style, Sabino & Tondini

Clarkson Potter, 300p, FIRST EDITON (US) 1985

Light signs of wear to jacket, small tear top of spine

Ballgowns, British Glamour since 1950, Stanfill and Cullen

V&A Publishing, 2012 first edition

Excellent condition, jacket showing v light signs of wear

Art Nouveau Furniture, Alastair Duncan

Clarkson Potter, 1982, FIRST American edition, 191p

Good condition throughout

Christie’s Arts and Crafts Style, Michael Jeffery

Pavillion Books, 2001, FIRST EDITION 192p

Good condition, light shadow along bottom of later pages

Hollywood Moments, Murray Garrett

Abrams, FIRST US edition, 2002, 176p EXCELLENT condition

The Encyclopaedia of Mammals, Edited by David W MacDonald

OUP, First edition 2006, 936 pages full colour throughout

Pristine interior, paper cover has tiny rip centre bottom front and small bending, plus light signs of wear.

Brilliant Effects, A Cultural History of Gem Stones & Jewellery, Marcia Pointon

Yale, 2009, possible first British Edition, 426p, press release included.

Jacket shows very light signs of wear, pristine interior (some discolouration to back end papers b/c of press release storage)

Paris, Edited by Gilles Plazy

Flammarion, 2003, possible first edition, 480 pages

Slipcased (basic cardboard, no decoration), and spine of jacket shows discolouration and rip to top of paper, small crescent-shaped discolouration on cover where thumb indent of case would leave it exposed, interior is pristine.

The International Book of Lofts, Elesin, Clife, Rozensztroch

Clarkson Potter, first US edition, 1986, 248 pages

Paper cover showing light signs of wear, interior pristine

Ancestors in the Attic boxed set: My Great-Grandmother’s Book of Ferns / My Aunt’s Book of Silent Actors, Michael Holyroyd

Pimpernel Press Ltd, 1st UK edition, 2017

Pristine condition

Modern Painters: Writers on Artists, forward AS Byatt

Dorling Kindersley, FIRST EDITION 2001, 352p

Good condition throughout

Biopic, Iggy Pop, by Gavin Evan

Canongate, FIRST edition, 2003, Excellent condition, black and white photography throughout, almost zero text.

Claudette Colbert, An Illustrated Biography, Laurence J Quirk

Crown Publishers, 1985 FIRST EDITION, 212 pp

Excellent condition

Making Marks, Sue Timney

Pointed Leaf Press, 176p, FIRST edition, 2010, die cut hard cover with images (ie: no paper cover) Excellent condition

Edinburgh, Mark Denton, intro Magnus Linklater

Frances Lincoln Ltd, 2009, First Edition, 192 p full colour throughout, rectangular format

Excellent condition, jacket shows light signs of wear around edges

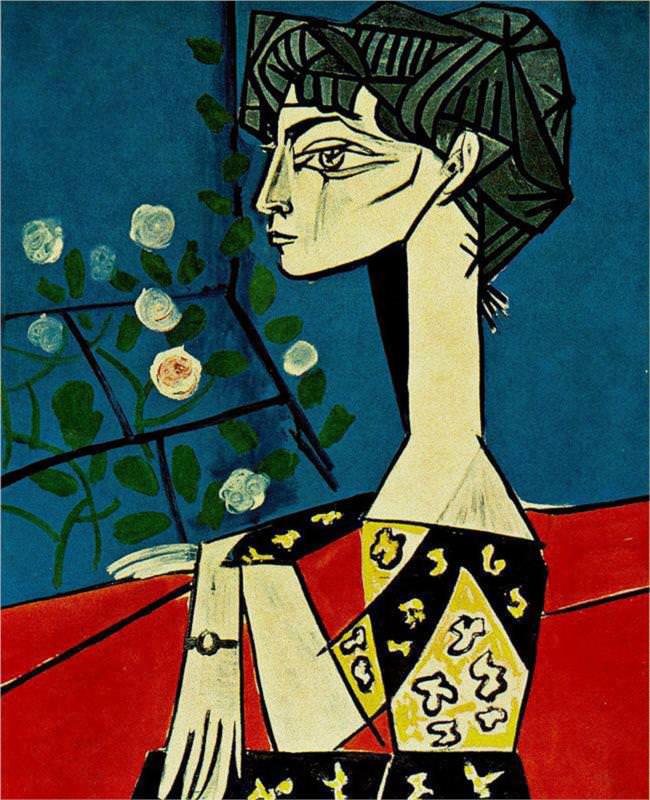

Picasso and his CollectionArt Exhibitions Australia, paperback with flaps, 312 p, over 250 illustrations; 2008 first edition

Excellent condition

Hats: An Anthology, Stephen Jones, Oriole Cullen

V&A, 128 p, FIRST edition, 2009

paper jacket has small tear at top of spine, small signs of shelving wear, otherwise excellent condition

A Life Drawing, Recollections of an Illustrator, Shirley Hughes

The Bodley Head, FIRST edition, 2002, 209 p,

Some mysterious reside on lower quadrant of paper jacket spine, otherwise excellent condition

British Design from 1948: Innovation in the Modern Age, Christopher Breward & Ghislane Wood

V&A, 2012, FIRST edition, 400p

Jacket shows light signs of wear around tops of flap, excellent

The Rose, Jennifer Potter

Atlantic Books, 521 p, 2010 FIRST Edition

Excellent condition

Charleston, A Bloomsbury House and Garden, Bell and Nicholson

Henry Holt, 1997 FIRST US EDITION, 152 p

Good interior condition, jacket showing small signs of wear

LIMITED OR SPECIAL EDITION

Pendulum, Portraits by Debra Hurford Brown

signed “With Love”, privately published, no jacket, oversized

Pristine condition

Lee Black Childers, Drag Queens, Rent Boys, Pick Pockets, Junkies, Rockstars and Punks

The Vinyl Factory, FIRST EDITION LIMITED TO 1000 COPIES WORLDWIDE

2012, 124p

Hardcover, printed with text and images, ie: NO paper jacket; in good condition

OTHER

The Scots, A Photo History, Murray MacKinnon, Richard Oram

Thames & Hudson, 224p, 2003

Excellent condition

Wilfred Thesiger in Africa, Edited by Christopher Morton and Philip Grover

Harper Press with the Pitt Rivers Museum, 280p, 2010

Excellent condition inside and out.

Period Details Sourcebook, Judith Miller

Mitchell Beazeley, 1999, 192 pp

Excellent condition, back of paper jacket shows minor signs of wear

The Art of the Tile, Jen Renze

Thames and Hudson, 320p, 2009

Jacket has small rip/bend lower right hand corner; small signs of wear on back; condition excellent otherwise

Rare Bird of Fashion, (Iris Apfel) Eric Bowman

Thames & Hudson, 2007, 159 pp

Excellent condition, jacket showing only light signs of wear from shelving

Embroidered Textiles, Sheila Paine

Thames & Hudson, 240p, 2008 (new edition of book f/1990); 508 illustrations, 362 in colour

Excellent condition throughout

Marilyn by Magnum, essay by Gerry Badger

Prestel, 2012 / pristine condition; short essay, mainly glorious photos

A Passion for Art, Art Collectors and their Homes, Gludowacz, VanHagen, Chancel, foreword Pierre Bergé

Thames & Hudson, 2005, 238p 208 illustrations in colour

Excellent condition throughout

David Bailey Locations, 1970s Archive, designed by Martin Harrison

Thames & Hudson, 2003 293 photographs 59 in colour, 260 pp, oversized trim size

Excellent condition, jacket shows light signs of wear from shelving

Matthew Roylston, BeautyLight

teNeues, 2008, oversized trim size, EXCELLENT condition

Elephant! Steve Bloom

Thames & Hudson, 100+ colour photos, 224 pp, oversized trim size, 2006

Excellent condition

Celebrity: photos of Terry O’Neill, intro by AA Gill

Little Brown, 2003, 192p EXCELLENT condition

Manolo Blahnick Drawings

Thames & Hudson, paperback with flaps; 134 illustration, 205 in colour, 2003

Excellent condition

Manolo Blahnick, Colin McDowell

Casell & Co, 199p, 2000

paper jacket shows signs of wear across top/bottom and doesn’t fold 100% beautifully around front, interior in excellent condition

Blahnik by Boman A Photographic Conversation, intro Paloma Picasso

Thames & Hudson, 2005, oversized trim size, full colour throughout

Excellent condition, minor signs of wear to back jacket, from shelving

In the Arts and Crafts Style, Barbara Mayer

Aurum, 2006 (UK edition of book published 1993 in US by Chronicle), 224 pages

Excellent condition

Quilting, Patchwork and Appliqué, Crabtree & Shaw

Thames & Hudson, 2007, 192p, 520 illustrations 504 in colour

Excellent condition

Duffy…Photographer

ACC editions, 2011, 208 pp

Good condition though spine feels slightly wonky, as if it was shelved badly at some point. Otherwise excellent throughout interior and jacket in good condition.

The Frampton Flora, The Secrets of Frampton Court Gardens Richard Mabey

Quercus, oversized trim, 208p, 2007 edition of earlier book (1985)

Excellent condition throughout

Tiaras Past and Present, Geoffrey Munn

V&A, small trim size, 128p, 2002

light signs of wear to jacket, excellent interior condition

Art Deco Fashion, Suzanne Lussier

V&A, small trim size, 2003, 96p EXCELLENT condition

Essential Art Deco, Ghislaine Wood

V&A, small trim size, 2003, 96p

light signs of wear to jacket, excellent otherwise

London Minimum, Herbert Ypma

Thames & Hudson, paperback with flaps, small trim size160p, 166 colour illustrations, 2010 edition of book originally published in 1980s

slight crease to front flap, otherwise pristine condition

Morocco Modern, World Design Series, Herbert Ypma

Thames & Hudson, paperback with flaps, 160p, 171 colour illustrations

Excellent condition throughout

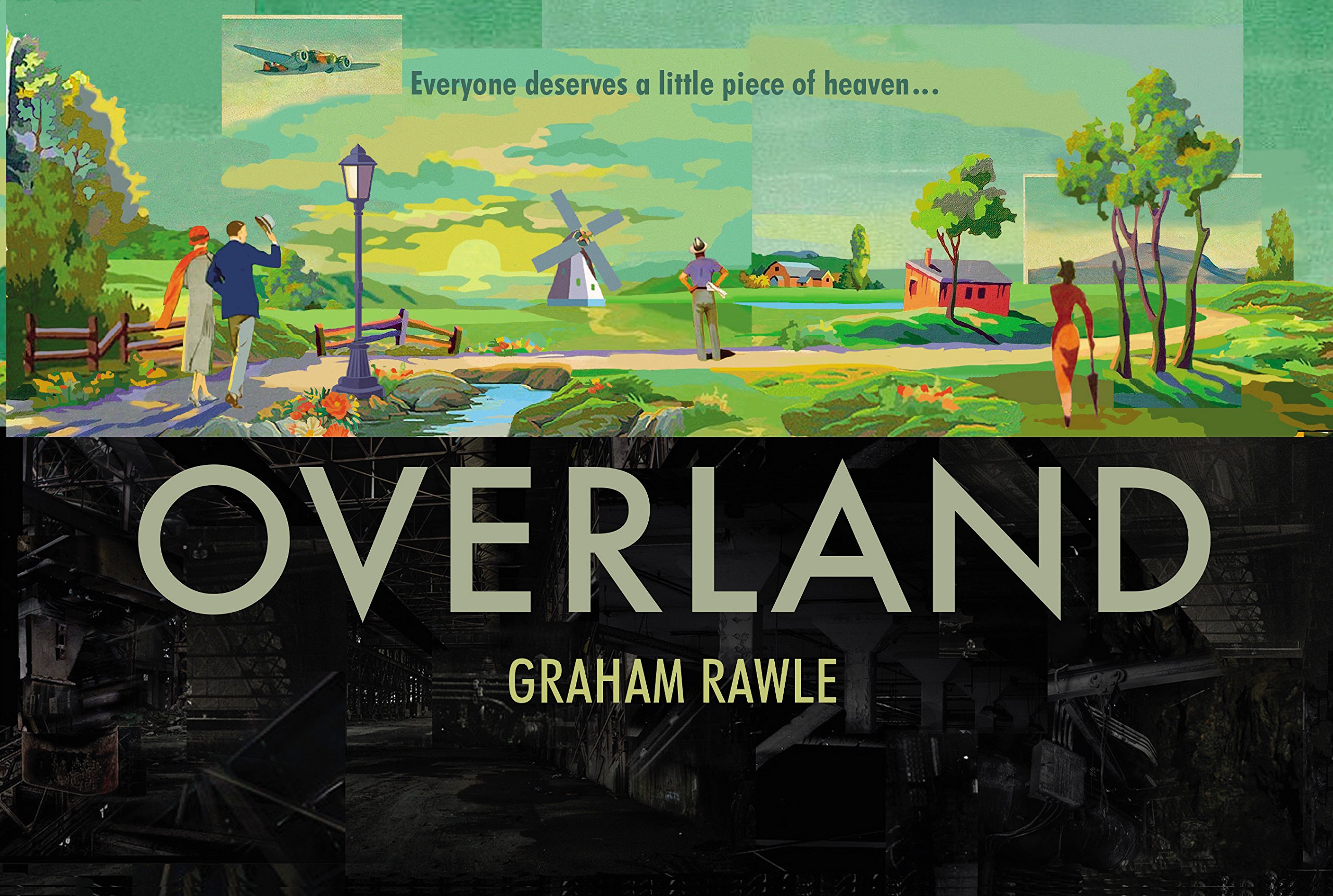

The American Circus, Edited Webber, Ames, Wittman [pictured above]

Bard Graduate Center for Decorative Arts etc.

Hardcover but published w/out paper jacket; 2012, 460 pages; exquisite book

Fred Astaire, Roy Pickard

Crescent Books, NY, 1985

Light damage to paper jacket, small tear upper left front, shelving wear, minor discolouration; COVER BENEATH that has been printed with the image, as well, so can be displayed without paper jacket; interior in good condition

Punk, Colegrave & Sullivan

Cassell, 2001, 400pp, oversized, weighs a ton

Bottom corners of book/jacket mildly bashed, small rip to back of jacket, otherwise in good condition throughout

David Lean, An Intimate Portrait, Sandra Lean & Barry Chattington

Andre Deutsch, 2001, 240p EXCELLENT condition

A Different Country, photographs of Werner Kissling, text Michael Russell

Birlinn/Polygon, 2002, 144 p

Excellent condition

Educating the Eye, Dutch Paintings of the Golden Age, Christopher Lloyd

Royal Collection Publications, pb with flaps, 196p small trim size, 2004

Good condition

A Life in Photography: Steichen

Bonanza Books (US), 254p, 1984 Edition of book originally published by Doubleday

Excellent condition, no tears, small signs of shelving wear

Chanel, Key Collections, Melissa Richards

Hamlyn, 2000, 176p,

Good condition, pages showing faint discolouration around edges, paper jacket signs of wear, one mark and a small tear near lower left front

Art Deco Textiles, Charlotte Samuels

V&A, 2003, 144p, GOOD condition throughout

20th Century Pattern Design, Lesley Jackson

Mitchell Beazeley, 2001, 224p;

GOOD condition overall: upper right hand back corner mildly bent both book and paper jacket, tiny damage to lower left of front jacket

Dress in 18th C Europe, Aileen Ribeiro

Yale, 2002 (revised edition), 318 p

Good condition, light bashing to upper righthand corner

Elizabeth Taylor: My Love Affair with Jewelry

Thames & Hudson, 2002; 280 illustrations, 185 in colour, 240p

Good condition, minor damage to top of paper jacket at spine

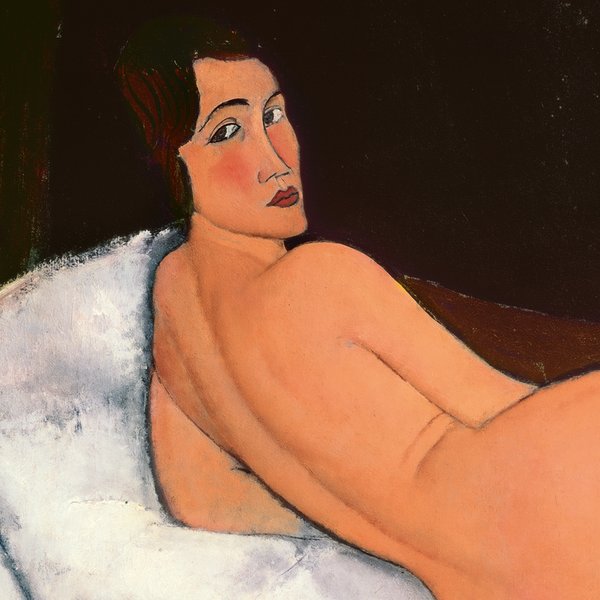

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Treuherz, Prettejohn, Becker

Thames & Hudson, 2003 [accompanied exhibition]

250p 190 illustrations, 140 in colour Good to excellent condition

Klimt’s Women, edited Natter and Frodl

Dumont Publisher, 2000 [accompanied exhibition], 256 p

Excellent interior, jacket showing signs of shelf wear and some creasing

Mary Queen of Scots, Susan Watkins

Thames & Hudson, 2001, 224p; EXCELLENT interior, jacket in good shape

Madame de Pompadour, Images of a Mistress, Colin Jones

National Gallery London (accompanied exhibition), 2002, 176 p

Good Condition